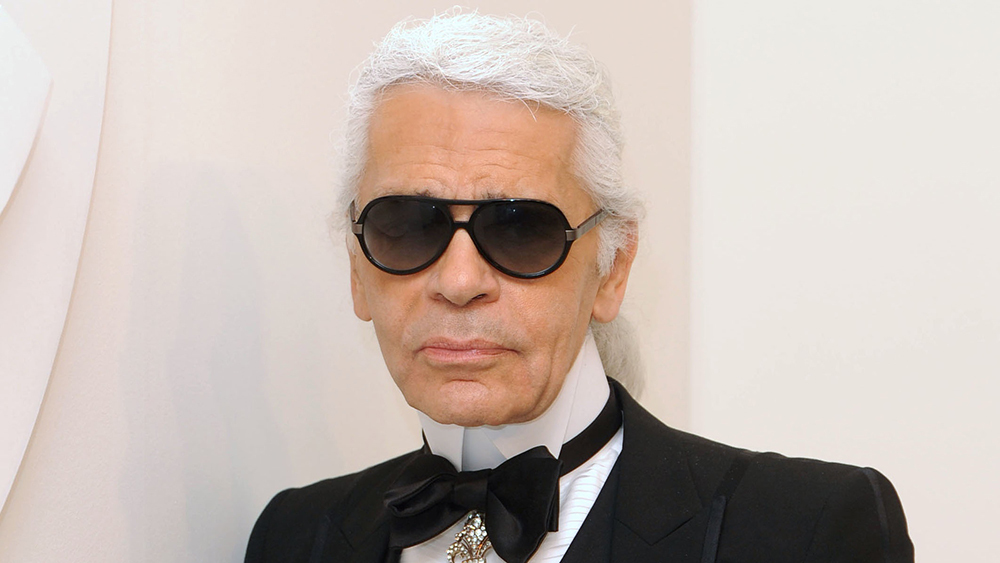

“Trendy is the last stage before tacky,” Karl Lagerfeld, the creative director of Chanel and Fendi, famously said – as one of the industry’s most remarkable fashion figures, he worked until his death on February 19, 2019 at the age of 85. In the same way, another great mind Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817–May 6, 1862) noted that, “We worship not the Graces, nor the Parcae, but Fashion,” in his 1854 classic Walden – that gave us the answers to the questions concerning Thoreau’s mode of life in the woods.

In Walden, Thoreau writes about fashion from the perspective of a philosopher – who loves nature, and lived alone in the woods of Concord, Massachusetts for two years and two months because of his longing for the essential facts of life and solitude. He considers that our garments have become more assimilated to ourselves since we wear them for the love of novelty and the opinions of others, but not for a true utility. He notes:

“No man ever stood the lower in my estimation for having a patch in his clothes; yet I am sure that there is greater anxiety, commonly, to have fashionable, or at least clean and unpatched clothes, than to have a sound conscience.”

And he further adds:

“Who could wear a patch, or two extra seams only, over the knee? Most behave as if they believed that their prospects for life would be ruined if they should do it. It would be easier for them to hobble to town with a broken leg than a broken pantaloon. Often if an accident happens to a gentleman’s legs, they can be mended; but if a similar accident happens to the legs of his pantaloons, there is no help for it; for he considers, not what is truly respectable, but what is respected.”

Indeed fashion should be timeless and different from the mainstream. Echoing the great poet and playwright Oscar Wilde’s insistence that “one should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art,” Thoreau’s idea on the way we dress reflects the collaboration between art and fashion:

“On the whole, I think that it cannot be maintained that dressing has in this or any country risen to the dignity of an art. At present men make shift to wear what they can get. Like shipwrecked sailors, they put on what they can find on the beach, and at a little distance, whether of space or time, laugh at each other’s masquerade. Every generation laughs at the old fashions, but follows religiously the new. We are amused at beholding the costume of Henry VIII, or Queen Elizabeth, as much as if it was that of the King and Queen of the Cannibal Islands. All costume off a man is pitiful or grotesque. It is only the serious eye peering from and the sincere life passed within it which restrain laughter and consecrate the costume of any people.”

In fact, the fashion industry has been working with the artists. In 1937, for instance, Elsa Schiaparelli designed a lobster print dress in collaboration with the surrealist artist Salvador Dalí for the Schiaparelli label. The collaboration between the two was a celebration of the relationship between fashion and art. But there are a multitude of factors that play a part in a costumer’s choice of clothing.

Thoreau further claims that taste of men and women is childish, savage, and merely whimsical. Thus, the manufacturers produce two similar patterns; one will be sold readily and the other lies on the shelf or becomes the most fashionable after the lapse of a season.

Pierre Bourdieu makes a very subtle contribution to this discussion of taste by his 1979 book Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (French: La distinction) – which indicates the relationship between cultural taste and class status. Bourdieu tries to move beyond the abstract relationship between consumers with interchangeable tastes and products; he claims that all cultural practices and preferences in literature, painting or music, are closely linked to educational level and to social origin. Conducting an immense survey across the French society in the late 1960s, he writes:

“A work of art has meaning and interest only for someone who possesses the cultural competence, that is, the code, into which it is encoded…Thus the encounter with a work of art is not ‘love at first sight’ as is generally supposed, and the act of empathy, Einfuehlung, which is the art-lover’s pleasure, presupposes an act of cognition, a decoding operation, which implies the implementation of a cognitive acquirement, a cultural code.”

As a part of his surveys, Bourdieu shows a photograph of an old woman’s hands to his sample group and ask them their opinions about it. Confronted with the photograph, a manual worker from Paris says:

“’Oh, she’s got terribly deformed hands’…There’s one thing I don’t get (the left hand) – it’s as if her left thumb was about to come away from her hand. Funny way of taking a photo. The old girl must’ve worked hard. Looks like she’s got arthritis. She’s definitely crippled, unless she’s holding her hands like that (imitates gesture) Yes, that’s it, she’s got her hand bent like that. Not like a duchess’s hands or even a typist’s! I really feel sorry seeing that poor old woman’s hands, they’re all knotted, you might say.’”

At higher levels in the social hierarchy, Bourdieu claims, the remarks become increasingly abstract:

“’The sort of hands you see in early Van Goghs, an old peasant woman or people eating potatoes’ (junior executive, Paris). ‘I find this a very beautiful photograph. It’s the very symbol of toil. It puts me in mind of Flaubert’s old servant-woman…That woman’s gesture, at once very humble…It’s terrible that work and poverty are so deforming’ (engineer, Paris).”

Perhaps the social and economic dimensions of the taste within society are accomplished and determined. And yet, amid the catastrophic outcomes of fast fashion trends to the natural environment, fashion preferences have consequences. Thoreau writes:

“Do not trouble yourself much to get new things, whether clothes or friends. Turn the old; return to them. Things do not change; we change. Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts.”